Our 2000 Interview With the Iowa Metal Band

This post originally appeared in the May perhaps 2000 situation of SPIN.

Slipknot have a motto: People = Shit. It is a straightforward adequate sentiment, but in some cases Iowa’s most renowned steel nonet like to reinforce the theory with visible aids.

“Shawn [Crahan, percussionist] determined to acquire a shit onstage in Virginia Seaside very last night time,” drummer Joey Jordison states. “I’m the only one particular down with that, so he threw a turd at me. When I went to take a shower, I experienced this big shit smeared on my sock.” Jordison (a.k.a. #1), is loudly discussing feces as he and bandmates Crahan (a.k.a. #6), vocalist Corey Taylor (a.k.a. #8), and bassist Paul Grey (a.k.a. #2) stroll as a result of the National Museum of Normal History in Washington. D.C., wherever they are scheduled to play a present tonight.

Not shockingly, the fellas are enthralled by the museum’s collection of animal skeletons, stuffed undersea specimens, and unsightly, overgrown bugs (“I just transpire to be fascinated with the bug environment,” Crahan states). Slipknot have crafted a brief but previously noteworthy profession as connoisseurs of the gross and grotesque.

Digital unknowns from Des Moines in advance of their next-stage stint on final year’s Ozzfest tour, Slipknot offered an remarkable 15,000 copies of their self-titled debut on the indie label Roadrunner the initial week right after its June release. The album has considering the fact that gone gold, irrespective of a relative absence of mainstream radio and MTV assist, as metal followers have slowly and gradually found the band’s squalling mix of machine-gun guitar missives, three-drummer tribal wallop, and otherworldly sample manipulation. Lyrically, Slipknot acquire goal at a litany of perceived betrayers, oppressors, and trash-talkers (“You ain’t shit, just a puddle on a bedspread,” Taylor rants on “No Life”). The overall spirit is righteous, chilly indignation, while times of perfectly-wrought imagery and repulsively loaded humor are woven into the apoplectic noise.

But it is the band’s conceptual underpinnings that make them glitter in the thrash bin. To start with there are the onstage theatrics, which have included smashing a goat’s coronary heart, heat-induced vomiting, and former welder Crahan partly severing a finger although showering the audience with sparks from an angle-grinder. “It’s not like we get out the goat coronary heart each and every night,” Jordison says. “The songs just brings it out of us sometimes.”

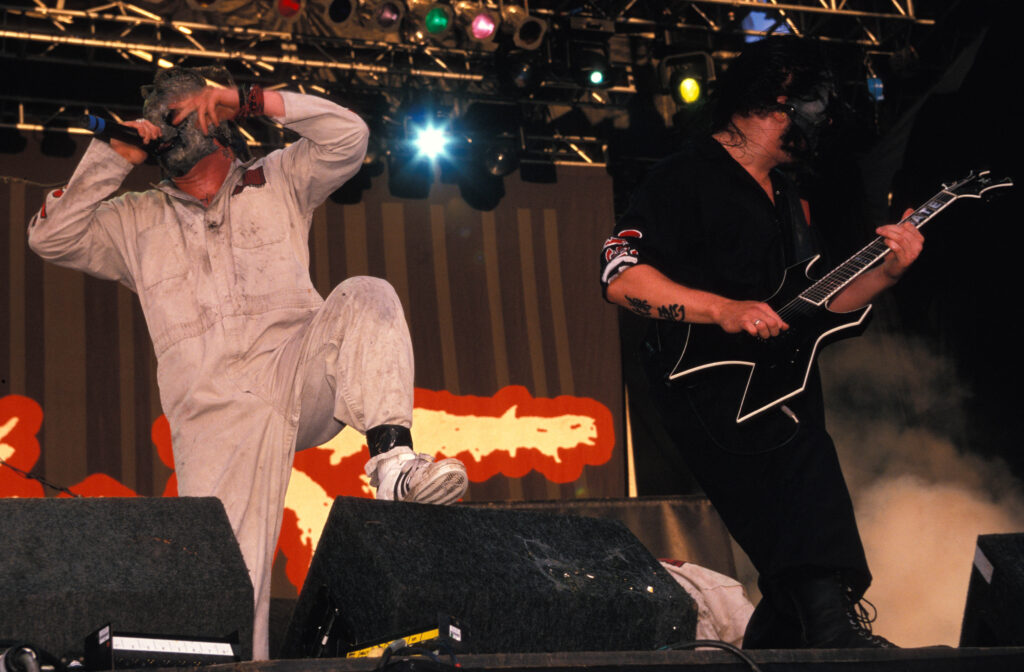

Most strikingly, however, there are the masks—grim rubber visages ranging from a leering pig encounter to a deranged clown to an exhumed Rasta corpse. The band say they dress in them to put the emphasis on their audio and not on their personalities, which is why they also activity matching jail-model coveralls and establish themselves by numbers as a substitute of names. But it in fact has the reverse effect: If the masks are not a surefire notice-grabber, then Crahan is the new Perry Como.

Marilyn Manson or Crazy Clown Posse could have told them that disguises get prizes in the new rock sweepstakes, while dressing up did not specifically function for fellow costumed metallists Gwar in the early ’90s. Gwar chief Dave Brockie sees the the latest public embrace of functions like Slipknot as a normal final result of grunge’s anti-showmanship ethos. “For a though,” Brockie states, “the taste was to glance as soiled and grubby as feasible. Then people received weary of that. Kiss set their makeup back on, and the floodgates burst open.”

Without having their surreal headgear, the associates of Slipknot glance fairly ordinary. If there’s at any time a sequel to the Flintstones movie, the bearish Crahan, 30 and a father of three, could be John Goodman’s stunt double. It is even feasible to think terminal great-person Taylor when he cops to a Yahtzee dependancy. The band’s practice of using swings at one particular another (Crahan and the comparatively puny DJ Sid Wilson (a.k.a. #) are repeated pugilistic opponents) is actually a indicator of solidarity. “I never chuckle with my very best pals,” Taylor claims, “but I get all around this band, which is my family, and I fucking die.”

Slipknot fashioned in 1995 when Des Moines rock-scene vets Jordison, Gray, and Crahan would fulfill for late-night time band method periods at the gasoline station where Jordison worked the graveyard shift. With a self-launched demo, Mate. Feed. Destroy. Repeat., under their belt, they propositioned Taylor whilst he doled out peep-booth tokens as a cashier at a downtown adult bookstore. “They ended up the baddest point to occur out of Des Moines,” Taylor says. “Sound-wise, musician-wise, depth-clever, you couldn’t touch it. And I hated them for it.” The natural way, he joined up.

Of course, becoming the best band in Des Moines is a little like winning a damp-T-shirt contest at a National Affiliation for the Blind convention. Modern A&R interest in the city—thanks to Slipknot’s success—notwithstanding, the band sprang from a breeding floor far better recognised for its copious Jell-O intake (the maximum for each capita in the nation) than its hunger for the musical arts. (The region’s greatest nightclub, Super Toad, is also in a family members-fun emporium that options a mechanical bull.) Taylor categorizes life in Des Moines as a “nonstop shit-feeding on fest. We had to make the loudest sounds possible.”

Slipknot eventually captivated the interest of neo-hesher producer Ross Robinson (Korn, Deftones), who signed them to his Roadrunner-dispersed I Am imprint and manufactured their debut. The tedium of the band’s hometown is not missing on Robinson. “The silence will either push you ridiculous or generate you to specific yourself,” he claims. “With them, it’s a little little bit of both.” Slipknot’s association with Robinson has bolstered the irksome-if-justifiable Korn comparisons that typically come their way. “It’s like Ozzy explained at the time,” Gray claims. “Everyone’s a thief no one’s totally first. It is just the way you acquire all all those items and develop a little something new.”

At minimum that sentiment is much more profound than the a person the headbanging godfather expressed when he first met Slipknot in the course of Ozzfest. “I go to hug [Ozzy] with a Coke in my hand, and it’s like dump—right down the fucking madman’s back again,” Jordison states. “He acquired pissed off, so you know what he did? He farted, and it stunk like a motherfucker.”

The performance this evening at D.C.’s 9:30 Club fails to generate any airborne turds, but it opens with an even better horror: Gary Wright’s treacly 1975 chestnut “Dream Weaver” wafting about the P.A. By the second verse, teenage cries of “What the fuck is this shit?” fill the air. Two youthful enthusiasts wave lit matches in ironic arena-rock appreciation.

The alternative of lead-in music is a pleasant counterpoint to the high-volume proceedings that adhere to. Bathed in strobe lights, Crahan, showing up far angrier than any gentleman in a clown mask has a suitable to be, shakes his fists, slowly and gradually attracts a drumstick throughout his throat in mock suicide, and manically humps his drum kit. Turntablist Wilson and percussionist Chris Fehn (a.k.a. #3) have a beer keg onstage, douse it with an unidentifiable liquid, and gentle it on fire as the band launch into “Wait and Bleed.” Wilson climbs the speaker stacks and executes a spiraling dive into the crowd, which catches him. The chaos pauses when Taylor holds up a latest difficulty of Teen Folks.

“I was pissed off like a motherfucker when I saw this,” the singer barks, exhibiting a Calvin Klein ad showcasing bare-chested Korn drummer David Silveria posing saucily. Taylor retains a match to the journal and shouts, “People like that are destroying audio!” The band kick into “Surfacing” and Taylor screams the chorus: “Fuck it all! / Fuck this environment! / Fuck all the things that you stand for!” as he stamps his boot-clad feet. After the clearly show, Wilson thoughtfully palms established lists to lingering lovers, drooling thick loogies on to the scraps. Backstage, the rancor above Silveria’s glamour-boy posturing carries on as Slipknot shake off the excess adrenaline.

“I hope I get out of the enterprise in advance of that at any time occurs to me,” Crahan says. “We experienced hope [for Korn], but it’s unfortunate, person. I’m disgusted.” Slipknot’s sole concession to vogue has been to order a backup established of coveralls. “The only thing we have ever needed to do,” Taylor says, “is to make the most ruling audio. And to eliminate most people.”